In the era of rapid development of generative artificial intelligence (GenAI), we are witnessing a fundamental transformation in the nature of intellectual work. Tools such as ChatGPT, Gemini, and Microsoft Copilot are permeating everyday professional practices. How do these technologies influence our critical thinking abilities?

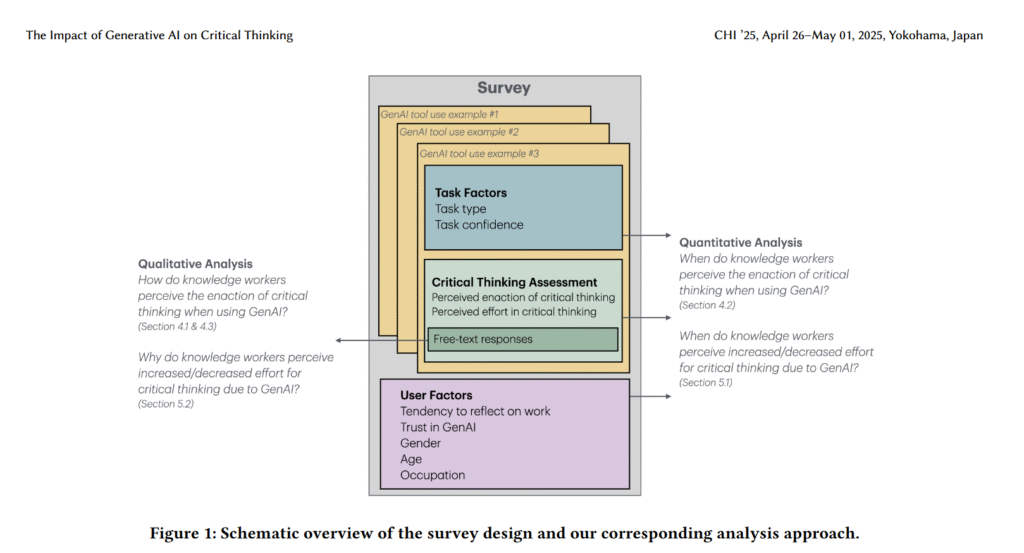

A newly published study by Lee and colleagues (2025) sheds light on this issue, offering an empirical perspective on the complex relationship between humans and machines during the intellectual processes accompanying knowledge management-based work.

The debate regarding the impact of new technologies on human cognitive abilities is not, of course, a novel phenomenon. As the authors of the report note, technologies such as writing (criticised by Socrates), printing (questioned by Trithemius), or calculators (causing concern amongst arithmetic teachers) have faced similar scepticism.

However, the scale and pace of GenAI proliferation, as well as its ability to perform tasks traditionally requiring cognitive skills, lend these concerns a new, more complex dimension.

The dialectic of efficiency and critical reflection

The findings of Lee and team’s (2025) study reveal interesting conclusions. Knowledge workers in the vast majority (55-79%) reported decreased effort associated with cognitive activities when using GenAI.

These tools automate routine tasks, facilitate information search and organisation, and offer personalised solutions to problems solved within the scope of employee responsibilities.

On the other hand, the research indicates a concerning tendency: increasing trust in AI capabilities negatively correlates with the effort to engage in critical thinking. This phenomenon has fundamental implications for information management and processing.

This paradox corresponds with what Bainbridge (1983) termed the “irony of automation” – the augmentation of routine tasks deprives the user of regular practise in exercising judgement, thereby weakening their cognitive abilities.

This may result in both cognitive laziness and negatively impact the future intellectual capabilities of a population eager to embrace the latest AI solutions.

In the context of GenAI, this irony takes on a new dimension: tools intended to support our intellectual work may paradoxically lead to the atrophy of our critical thinking abilities.

Cognitive metamorphosis in intellectual work

The study by Lee and colleagues (2025) demonstrates that GenAI does not so much eliminate critical thinking as redefine its character.

There is a distinct shift in cognitive effort across three dimensions:

- From information gathering to verification – instead of laborious fact-finding, knowledge workers must now focus on evaluating the credibility of information provided by AI.

- From problem-solving to response integration – rather than independently developing solutions, adapting and contextualising AI suggestions becomes crucial.

- From task execution to process supervision – the worker’s role evolves towards that of a “steward” of the process, responsible for formulating goals, directing AI actions, and assessing the quality of outcomes.

This metamorphosis in the nature of cognitive work poses a question:

Are we witnessing a pro-cognitive human-AI synergy, or rather a subtle and gradual erosion of our cognitive competencies?

The answer, as the study suggests, depends on a complex interplay of factors, including workers’ self-confidence, their general tendency towards reflection, awareness of technological limitations, and self-awareness of mental processes whilst working with GenAI.

Metacognitive confrontation with the black box

A particularly interesting thread emerging from the study concerns the metacognitive challenges that GenAI presents to workers managing and processing information in their daily work.

Tankelevitch and colleagues (2024) describe this as “metacognitive demands”.

Working with generative AI systems requires not only understanding one’s own cognitive processes but also forming mental models of how the AI “black box” functions.

The study reveals that workers perceive critical thinking when using GenAI as a set of actions aimed at ensuring the quality and purposefulness of work, including:

- formulating clear objectives and optimising queries;

- verifying results according to objective and subjective criteria;

- selective integration and adaptation of AI responses.

Barriers inhibiting critical thinking

Importantly, the authors identify three key barriers inhibiting critical thinking and engagement in mental processes amongst workers participating in the Microsoft study:

- awareness limitations (e.g., excessive reliance on AI);

- lack of motivation to maintain high-quality work (e.g., time pressure);

- deficiencies in AI work management skills (e.g., difficulties in obtaining satisfactory responses).

These barriers indicate the need for a more holistic approach to designing, implementing, and educating on the use of GenAI systems in work environments.

Implications for education and technology design

The findings of Lee and colleagues’ (2025) study carry significant implications for both educators and technology designers.

From an educational perspective, it seems necessary to develop new approaches to teaching critical thinking competencies that would account for the specifics of working with GenAI.

Traditional frameworks, such as Bloom’s taxonomy, require reconceptualisation to reflect the new dimensions of information verification, response integration, and AI process supervision.

The study results suggest the need to develop GenAI tools that would not only increase efficiency but actively support users’ mental engagement in the process.

As the authors note, worthy of consideration are:

- Trust recalibration mechanisms that would help users maintain a healthy balance between self-confidence and confidence in AI work outcomes;

- Proactive and reactive interventions emphasising the need for critical thinking;

- Features facilitating verification and enhancement of AI responses.

Ethical dilemmas of cognitive symbiosis

Lee and colleagues’ (2025) study also provokes reflection on the ethical aspects of the human-AI relationship in the context of cognitive work.

If GenAI indeed changes the nature of critical thinking, who should bear responsibility for potential errors or shortcomings? How might one balance the benefits of automation with the imperative of preserving cognitive autonomy?

Furthermore, how can we prevent the deepening of cognitive inequalities between those who can critically collaborate with AI and those who become increasingly dependent on its guidance?

These questions take on particular significance in light of the study’s findings regarding the correlation between self-confidence and critical engagement.

If higher self-confidence promotes critical thinking, there is a risk that the benefits of GenAI will be asymmetrically distributed in favour of individuals already possessing high cognitive capital, and to the disadvantage of those who most need intellectual support.

Conclusions – towards augmentation instead of abdication

Lee and colleagues’ (2025) study offers an empirically grounded perspective on the complex relationship between GenAI and critical thinking in knowledge management-based work.

The results suggest that GenAI can both support and undermine critical thinking abilities, depending on the context, user characteristics, and technology design.

In light of these findings, a vision of cognitive augmentation rather than abdication seems desirable – using GenAI as a tool that enhances, rather than replaces, human critical thinking abilities.

Achieving this vision, however, requires conscious effort from all stakeholders: technology designers, organisations implementing these tools, educators training future workers, and the users themselves.

Paradoxically, in the era of cognitive automation, the ability to think critically becomes not less, but more important.

It is no longer just about the ability to analyse, synthesise, or evaluate content, but also about metacognitive awareness of one’s own limitations and the potential of AI technology. As one study participant put it: “AI doesn’t replace my thinking, but it requires me to think in a different way”.

This transformation in the nature of critical thinking in the GenAI era constitutes a fascinating field of research and a practical challenge for the entire population.

Our collective response to this challenge will determine whether generative artificial intelligence becomes a catalyst for human cognitive and technological development, or a monument to human cognitive dependence on machines.

Bibliography

- Bainbridge, L. (1983). Ironies of automation. In Analysis, design and evaluation of man–machine systems. Elsevier, 129–135.

- Lee, H-P., Sarkar, A., Tankelevitch, L., Drosos, I., Rintel, S., Banks, R., & Wilson, N. (2025). The Impact of Generative AI on Critical Thinking: Self-Reported Reductions in Cognitive Effort and Confidence Effects From a Survey of Knowledge Workers. CHI ’25, Yokohama, Japan.

- Tankelevitch, L., Kewenig, V., Simkute, A., Scott, A.E., Sarkar, A., Sellen, A., & Rintel, S. (2024). The Metacognitive Demands and Opportunities of Generative AI. Proceedings of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems.

- Sarkar, A. (2024). AI Should Challenge, Not Obey. Communications of the ACM, 67(10), 18-21.

- Simkute, A., Tankelevitch, L., Kewenig, V., Scott, A.E., Sellen, A., & Rintel, S. (2024). Ironies of Generative AI: Understanding and Mitigating Productivity Loss in Human-AI Interaction. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, 1-22.